Jürgen Heinemann: 'Visual condensations of existential questions'

Jürgen Heinemann (1934–2025) passed away at the age of 91. A German photojournalist and documentary photographer, he gained international recognition in the 1960s and 1970s for his haunting black-and-white photographs of Spain, Asia, Africa, Latin America, and other regions of the world.

His work is characterised by a humanistic visual language that focuses on people in their working environments, families in specific life situations and children between carefree moments and threats. His photographs capture the defining moments of social reality, where faith, love and hope play a central role. The camera does not function as a detached instrument of observation, but rather as a mouthpiece for existential themes.

'Pictorial condensations of existential questions' – this is how Heinemann himself described his photography. His works are not mere reportages, but visual questions about human existence, mindfulness, and the conditions of life. This fundamentally distinguishes his work from purely neutral documentation, giving it a reflective, almost philosophical dimension.

Many of his travels and photo series were undertaken for church aid organisations such as Adveniat and Misereor. This resulted in a particular focus on social injustice, poverty, and the living conditions of marginalised population groups. Heinemann's photography aimed to inform and sensitise, but above all to convey empathy.

The social misery and political oppression of the disenfranchised are never displayed voyeuristically in his images. Instead, his photographs serve as testimonies to historical and structural violence, such as the long-term consequences of colonial land grabbing. His photographs are not an end in themselves for aesthetic purposes, but rather aim to reveal the reality and dignity of the people depicted. Heinemann thus stands in the tradition of humanistic photojournalism, in which the photographic image is a window onto social reality.

Heinemann worked almost exclusively in black and white, considering this choice integral to his aesthetic strategy. Through high-contrast exposure and a deliberate condensation of light, he created images of great visual presence and emotional depth. The interplay of light and shadow not only serves form but also reinforces the density of content and the existential tension of his motifs. Form and content form an indissoluble unity.

Technically, he often used a Leica camera and, in the spirit of Henri Cartier-Bresson, placed great importance on the 'decisive moment': the instant when form and emotion converge to create a unique pictorial event. Focusing on spontaneous, authentic events was an integral component of his photographic methodology.

Encountering Jürgen Heinemann

I met Jürgen Heinemann twice: once at his flat and studio in Potsdam, and once at Manoel Nunes' gallery in Cologne. He was a modest and rather introverted person who suffered from asthma and chronic bronchial problems. He also suffered from a progressive eye condition that worsened dramatically over the years, which was an especially painful limitation for a photographer.

We spoke on the phone at irregular intervals. He spoke earnestly about his desire to organise, digitise and systematically structure his extensive photo archive by country.

Behind every photograph was a story.

After coordinating the transport of photo historian Helmut Gernsheim's contemporary photo collection from Lugano to the Reiss-Engelhorn Museums in Mannheim during the early stages of the International Photography Forum that I had recently set up, I worked with Robert Häusser to catalogue, inventory and archive the Gernsheim Collection's holdings. Among the numerous works was a collection of photographs by Jürgen Heinemann.

This was my first intensive encounter with his black-and-white works, characterised by light-dark contrasts of great formal consistency, with each image precisely formulated and condensed in terms of design. The signature style of the Otto Steinert School — 'subjective photography', which focuses on personal vision — is evident. Heinemann studied under Oskar Holweck and Otto Steinert at the Werkkunstschule Saarbrücken, and subsequently at the Folkwang University of the Arts in Essen, from 1959 to 1962. His images are socially critical yet imbued with a deep sense of empathy and compassion, almost resembling a modern Pietà concept — a silent lament for enclosed existences with no emergency exit. Far from being kitschy, they are imbued with faith, fatalism, and a rebellious élan vital.

Impressed by this visual language, I visited Jürgen Heinemann in Potsdam in November 2008. This followed the ‘Photography in the Museum’ symposium organised by the Berlin Art Library, at which I was a speaker. I recorded our conversation on film. The idea of curating an exhibition of his work began to take shape. In his studio, he showed me numerous series. I was particularly impressed by his series of images of Holy Week (Semana Santa) in Seville in 1960. Heinemann had documented the sombre, almost medieval-looking processions of penitential brotherhoods during the religious rituals of Easter week. The hooded figures and their austere gestures, combined with the nocturnal atmosphere, create images of great formal and emotional intensity.

In this series, the black of the silver gelatine prints has a peculiar gravity. The deep blacks do more than merely function as shadows; they seem to absorb bodies and space entirely, like black holes within the image. In this gloom, Heinemann's photography evokes the visual world of Francisco de Goya, where the demonic is not depicted but born of the darkness itself. Goya's demons appear as projections of human fear, as seen in the Pinturas negras. In both artists, the threatening atmosphere is created not through narrative drama, but through formal condensation and darkness, from which figures emerge or threaten to sink.

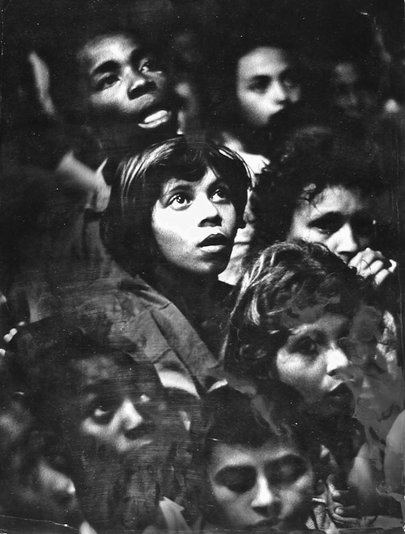

Heinemann rightly received the World Press Photo Award in 1963 for his black-and-white photograph Brazilian Children During a Religious Ceremony. This image is a prime example of his ability to capture an emotionally charged moment in a formally clear manner with great documentary value. A ray of light illuminates a girl's face, lifting it out of the surrounding darkness. The other children remain in the shadows, not absent but lingering in silent devotion.

As in Goya's sombre imagery, enlightenment does not appear as salvation, but as a fleeting moment of visibility. The blackness of the print has weight; it envelops the light, making it clear that every revelation remains precarious.

In addition to their existential gravity and formal austerity, Heinemann's subjects are imbued with a subtle, deeply human humour. This is evident in the photograph of a group of laughing, semi-neglected street children in Portugal, for example, who imitate the adult world in front of the camera with playful macho behaviour. One of them demonstratively puffs on a cigarette, posing as the supposed 'big boss' and thus reducing the gesture of power to absurdity.

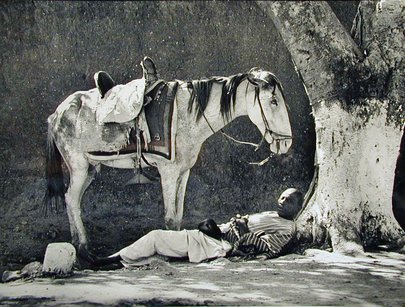

Similarly, in photographs of laughing children in Africa, they observe something with a mixture of wonder and curiosity, reacting with mischievous delight to an event that the viewer cannot see. Another example is the image of a rider dozing on the ground while his horse stands patiently beside him – a scene of quiet irony and casual poetry.

Rather than representing a break, these photographs provide a deliberate counterpoint within the overall body of work. They enrich Heinemann's imagery by adding moments of lightness, showing that his humanistic gaze was not solely focused on suffering and distress, but also on dignity, wit, and the fragile happiness of everyday life.

I deeply regret that the exhibition of his works that I would have liked to curate did not ultimately come to fruition. Renovation work at the museum, coupled with the foundations' austerity measures resulting from the zero-interest-rate policy, made many things difficult and ultimately thwarted this exhibition plan.

Hopefully, this quiet work will be given a space where it can once again be seen, questioned and understood. I very much hope it will be.

Prof. Dr. Claude W. Sui, 9 January 2026